By Garrett Hein

Editor's note: Garrett Hein is the service manager at McLain Cycle & Fitness in Traverse City, Mich. He attended last week's USA Cycling Bill Woodul Race Mechanic's Clinic in Colorado Springs and agreed to write about his experience for BicycleRetailer.com.

COLORADO SPRINGS, CO (BRAIN) — U.S. Bicycling Hall of Famer Bill Woodul started the race mechanic's clinic because he wanted to share his knowledge and experience. Woodul, who died in 1996, pioneered neutral support at U.S. road races, and is probably best known for attending all the major U.S. events in the Campagnolo wagon in the 1970's and 80's.

Woodul's pedogogy drives the clinic today, and any question for the instructors is on the table. Their contained knowledge and experience is so grand that it in no way can entirely fit into the four and a half days of lectures. But the proximity to the industry leaders that teach here is staggering. While they lecture, it's really best to just listen and take notes, but then you get to eat with them. It is a rare thing, really, to catch industry icons at a lunch table and at the same time be able to talk to them, prod them with questions or advice. It's unique and priceless.

It seems like anyone who is anybody in the industry has gone through the class, and a bunch of those guys come back as instructors. Calvin Jones (Park Tool), Andy Stone (Team Type 1), T.J. Grove, Ric Hjertberg (of Wheelsmith and Mad Fiber fame), Matt Bracken (president of Pedro's, previously Independent Fab), Butch Balzano (SRAM NRS), and Chip Howat (who literally wrote the book, a dense 250-page treatise on the responsibilities of race mechanic) are there. But that's a short list. We heard from Shawn Farrell (USAC Technical Director), Bernard Condevaux (a brilliant soignuer), and Caleb Fairly (yes, the racer from Garmin-Sharp).

This is where the business side of professional wrenching becomes clear. A race mechanic's technical training is all those years at the bike shop (getting into the clinic requires two years experience, minimum). At a race, they become much more than that. It's their job to exude calmness, pass it on to the riders, keep things under control and moving smoothly. If they do things right, their work is largely unnoticed. But if they do things wrong, an entire race can be ruined.

The clinic instead teaches the philosophy behind the life and career of a race mechanic. Which, conveniently, extends to neutral or mass-ride support. The day-to-day business of working for a team or race is hyper-demanding, as it's stressed on the students, and the clinic is structured to mimic the role. Over four and a half days, 42 hours are consumed by classes, and who knows how many more are eaten by studying and debating the challenging exam.

A large number of questions on the examination are relatively easy, straightforward, research driven questions, i.e. they can be looked up in the USAC or UCI rulebook, or they're printed in Chip Howat's textbook. But the rest, and certainly a majority, are more vague, and exist ethically grayer areas. They are snap judgement decisions made in real world scenarios, and the students are expected to replicate the correct actions. The debate over whether or not to change a bike or cut a brake cable is endless, and ultimately the answer comes down to evaluating yourself as a person and a mechanic and choosing the corresponding answer, which isn't necessarily the correct answer.

A large number of questions on the examination are relatively easy, straightforward, research driven questions, i.e. they can be looked up in the USAC or UCI rulebook, or they're printed in Chip Howat's textbook. But the rest, and certainly a majority, are more vague, and exist ethically grayer areas. They are snap judgement decisions made in real world scenarios, and the students are expected to replicate the correct actions. The debate over whether or not to change a bike or cut a brake cable is endless, and ultimately the answer comes down to evaluating yourself as a person and a mechanic and choosing the corresponding answer, which isn't necessarily the correct answer.

That turns out to be a good thing because the ensuing debate between the mechanics and instructors is even more educational. The larger point is that being a race mechanic is hard not just because the hours are long and exhausting, but because making a decision in a stressful situation that could greatly affect the outcome of a rider's race is something that you can, at best, only sort of adequately prepare for. There will undoubtedly be some sort of race scenario that one might be in that doesn't reflect anything before it, and that situation could very likely end up on the exam to be tirelessly debated in future classes.

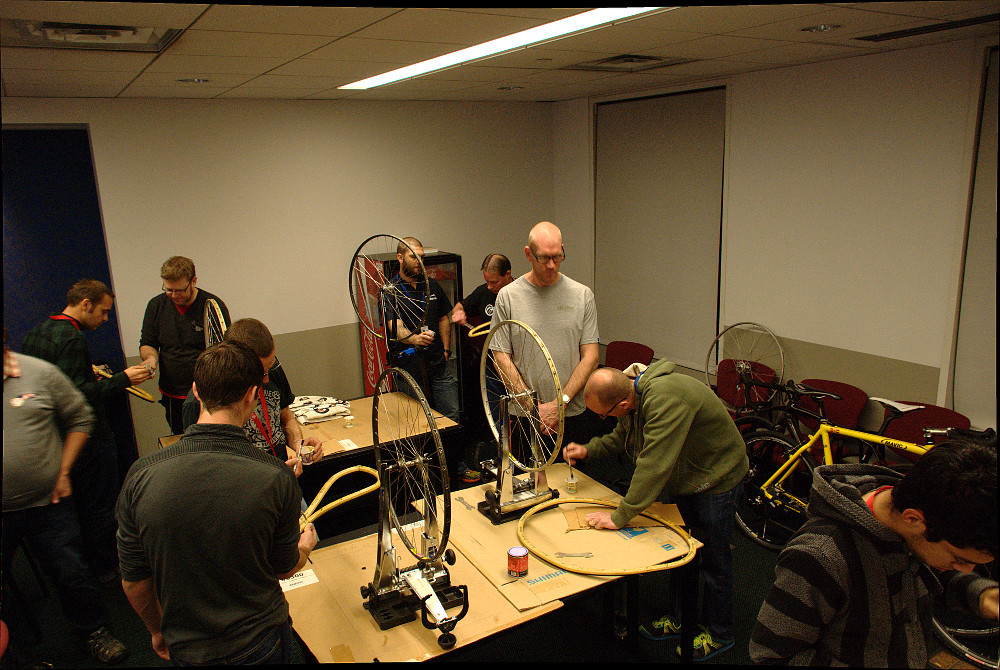

The clinic itself is broken up into shorter classes in small groups dealing with more than thirty topics. And, further, each class ends up discussing even more sub-topics depending on who the expert is at the front of the room and what information a question can drag out of them. Everything from Pro Road Team Support to Gran Fondo neutral support is covered. You learn DOT rules and regulations, the art of the wheel change, how to clean a bike quickly, the challenges of supporting para athletes, and on and on. The weight of information delivered is exhausting.

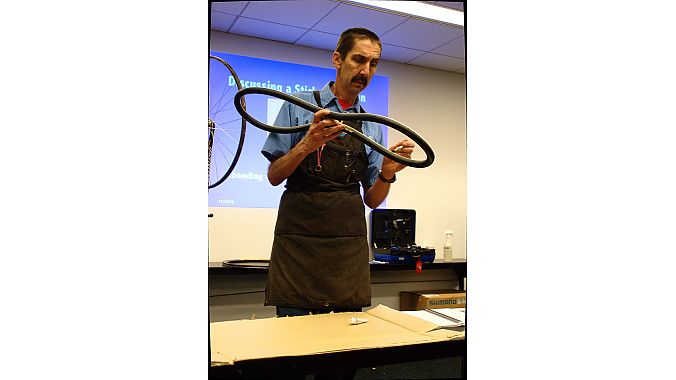

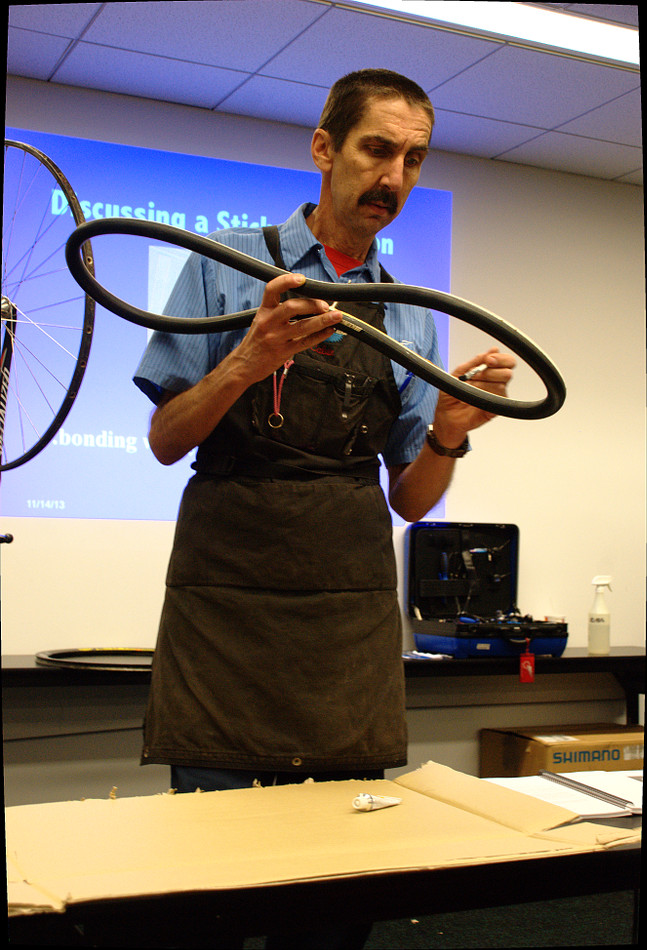

Even though no one is here to learn how to install a chain or adjust a derailleur, there is still technical education. There are lectures on disc brake technologies, suspension tuning, wheel building, and of course gluing tubulars, which seems to be 70 percent of a race mechanic's job.

The Bill Woodul Race Mechanic's Clinic is strongly moving forward and it remains hugely important to the cycling industry in the United States and the world. American mechanics in the professional ranks are respected, thanks largely to the unification of philosophy and purpose that the clinic teaches.