Last time, I proposed that bike and equipment companies can succeed and grow in a flat market by shifting focus from pushing units to winning — and keeping — customers; and that they can do this by offering a better customer experience, starting at the in-store level. The current installment unpacks that idea in a little more depth, including the question, “how do we pay for all this stuff?”.

The whole units-versus-customers equation boils down to three fundamental propositions (which are well-known to smart retailers but seem difficult for most bike brands to get their brains around):

- It's cheaper and ultimately more profitable to sell additional products to your existing customers than it is to recruit new ones (Cost of Acquiring Customers). The flip side of this is the total value of the customer over the life of their relationship with your brand (Lifetime Value, also discussed in the previous link) and how it offsets CAC.

- The two items above are even more true for markets where a) there aren't a lot of new customers entering, b) there's an aging customer base, and c) in mature product categories where brands are at or near parity in terms of features and pricing. Examples would include mobile phones, automobiles and, yes, Bike 3.0.

- With the semi-exception of Trek (which we will discuss in just a bit), the industry's large suppliers seem either ignorant of or indifferent to items 1 — 2. This creates a huge opportunity for everyone else, particularly smaller brands who can only succeed by taking market share away from larger competitors.

Investing in lifetime customers = investing in lifetime retailers

If you're an equipment or bike brand selling through independent retailers, you need to understand something. No matter how much money you spend luring prospective buyers through your dealer's door (Cost of Acquiring Customers), once the consumer steps inside, the retailer is in control of the buying experience. More importantly, surveys across related industries — from bikes and motorcycles to cars and boats — show the retailer is by far the single most critical factor in determining how happy a customer will be with their purchase, and how happy they will be with the purchased brand over the long term.

Happy customers are repeat customers. Repeat customers are good, because they deliver much higher Lifetime Customer Value for only slightly higher cost of acquisition, which ultimately equals higher profitability. Everybody wins, and the principle has been proven across all kinds of product and service markets. But to my knowledge, no brand in the cycling industry directly incentivizes retailers for delivering an exceptional — or even an adequate — buying experience to customers.

Retailers tell me a semi-exception to this point is Trek, and that exception is well worth talking about, because it begins to show how other brands can put comparable programs into place.

"(Trek's) goal is to give us the tools to achieve our potential for being the best dealer in the area. There is a score card where Trek rates every dealer against Key Performance Indicators for store appearance, percentage of employees who've gone to Trek University, and so forth. You can't get to the higher dealer levels and receive better terms and pricing and unless you're doing a better job of putting cycling forward to the public. That's been in place for a decade."

That's Mike Jacoubowsky talking, owner of Chain Reaction Bicycle Shop in Redwood City, California. He's an NBDA board member, a 40-year Trek retailer in one of the most competitive markets in the U.S., and a longtime Trek evangelist.

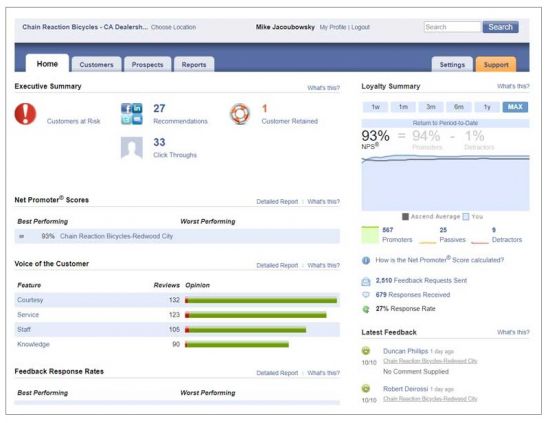

In addition to KPIs, the other tool he identifies is Listen 360, a customer comment aggregator. According to its website, Listen 360 is used at over 20,000 business locations to survey, collect, and analyze customer engagement and customer feedback. The software gives participating retailers a multifunction dashboard to review what customers are saying about their businesses, interact with them, and monitor overall satisfaction ratings over time.

It's an impressive tool set, but Jacoubowsky was initially skeptical. "It's kind of scary at first, because you don't know what you're in for, but eventually things level out," he says. "It keeps you on your toes. We've all had issues with Yelp because of its anonymity. But if a dealer believes that metrics are wrong and they shouldn't be rated, I think that dealer is not living in the present time.

It's an impressive tool set, but Jacoubowsky was initially skeptical. "It's kind of scary at first, because you don't know what you're in for, but eventually things level out," he says. "It keeps you on your toes. We've all had issues with Yelp because of its anonymity. But if a dealer believes that metrics are wrong and they shouldn't be rated, I think that dealer is not living in the present time.

"Every customer who gives us an email with their purchase gets an invitation to rate us through Listen 360," Jacoubowsky says. "About 30% do. And if they rate the business highly, the system encourages them to push that review to Google, Yelp or Facebook." Not only does the "push" promote positive reviews of the Chain Reaction, he says, it can also increase his shop's page rankings on those services as well.

Although Jacoubowsky says he has become a big believer in Listen 360 and uses the service faithfully, there is no direct incentive from Trek for him to for score well, or even for using it in the first place.

"Trek has never told us that big brother is watching, and there are no carrots or sticks involved. But since Trek is providing the platform, you have to conclude they see what goes on with it. I don't see that as a bad thing. Accountability in a feedback loop improves success." The service normally costs money, he explains, and Trek covers all the costs. "They offer this as an opt-in resource, but they certainly encourage us to use it."

Flipping the script starts with flipping the relationship that writes the script

The larger question, for purposes of this piece, is why wouldn't Trek (or any other brand) want to reward retailers who help them build more loyal — and ultimately, more profitable — customers? I've been asking questions like this for more than thirty years in this industry and the best answer I've found to date is, the bicycle business is very good at doing what it's always done. Which is to say, doing what it's always done.

But as pointed out earlier, that same inertia also represents a huge opportunity for smaller, more agile brands willing to invest in an antidote to the business-as-usual mentality that relentlessly stacks the deck in favor of the largest players.

There are literally dozens of ways to build better a customer experience, but they all have three phases: setting customer expectations before the sale is made (from both supplier and retailer ends); the actual sales experience (which for bike brands especially, focuses on the retail environment); and maintaining the relationship after the sale is made and into future sales (again, the responsibility of both parties).

What's fundamentally different about this approach is that it involves a tighter relationship between brand and retailer, and one that's almost antithetical to the increasingly common industry notion of retailers as passive fulfillment centers. Perhaps ironically, it's the sort of relationship that was promised at the beginning of the Bike 3.0 era, but has continually eroded over the intervening two decades. To put it another way, it's a business model that puts the dealer at the center of the relationship between brand and consumer.

Brands can implement owners groups and customer retention initiatives and reward retailers who deliver higher customer satisfaction ratings, but until the basic relationship between supplier and bike shops changes, nothing changes. And paradoxically, this change needs to happen at a time when the prevalent model is for brands to remove retailers from the sales process as much as possible.

The devil's not in the details; it's in paying for them

If you think dealer pricing structure in the bike business is Byzantine, you need to spend some time in the auto industry, where most major car brands reward dealers for things like retail branding, best sales practices and overall customer satisfaction (as measured by surveys) through a practice called holdbacks.

As the name implies, the holdback is a piece of the retailer's margin which is "held back" from the initial invoice and returned in the form of a discount after the sale is made. (It's also why the "invoices" posted in the windows of lot cars are significantly higher than what the retailer actually ends up paying for those cars, but that's another story.) Typically, holdbacks represent between zero and three retail margin points and, as in the bike business, those points can make a huge difference to a car dealer's bottom-line profitability.

For competitive purposes relative to other bike brands, a holdback program for bike retailers who deliver a better customer experience would have to come in addition to current dealer margins, which means they would become a net cost to the brand. My suggestion is that brands fund holdbacks (and other customer experience initiatives) by making them a part of the overall marketing budget, even at the expense of traditional programs like advertising, race teams, video extravaganzas and so forth. This is not typical bike industry accounting practice, but if you think about where the cost centers are, it's sound bookkeeping.

The economics are straightforward: the value of traditional "brand-building" marketing decreases as a market stagnates. But if you increase Customer Lifetime Value, you don't need to spend as much on traditional razzle-dazzle Customer Acquisition.

Best of all, by using holdbacks and smart metrics, brands only pay for the improved customer experience that individual retailers actually deliver. And, unlike traditional marketing, gains from improving CLV can be directly measured.

However, instead of putting the full onus on brands to step up, let's close by standing the question on its head: how many retailers would be willing to devote more time and effort to providing a higher level of customer experience for a particular brand if they earned 2-3 additional margin points relative to that brand's competitors?

Retailers, we need to hear from you on this.